John Kotula presents: Story Time

John Kotula is an artist, writer, and arts educator who lives in Peace Dale. His training in the arts included stints at a number of colleges and workshop programs, among them Queens College, Brooklyn Museum Art School, RISD, and Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center. He exhibits his work in galleries, but is also interested in sharing what he does in other ways, such as giving his work away, unauthorized public display of the art, mail art, and the internet. Other current artistic interests include narrative artwork such as comic books, work that is created in collaboration with other artists, murals, and art making in Latin America.

John is an active curator. Shows through Hera Gallery have included Crossing Boarders/Cruzando Fronteras, a show about immigration, Miracle Due, Gonna Come True, a show of Latin American art organized in conjunction with the Courthouse Center for the Arts, Young Artists and Their Mentors, a series of three shows exploring the role of mentoring in the development of young artists and TechnoCraft, where high tech meets hand made, a Hera Gallery show presented at The Jamestown Arts Center. John also curates the ongoing Hera Gallery project The World’s Smallest Art Gallery, art displayed in a kiosk on the bicycle path in Peace Dale. John’s blog is called Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man.

I'm very excited to present Story Time to you! All of the pieces in this exhibit at Hera Gallery combine images and words, in a variety of ways to share stories that I have experienced, developed and presented over many of years. The show includes drawings, paintings, video, performance, books, collaboration, and participation. Some of it is quite personal and, of course, since you know me, a lot of it is goofy... sometimes its personal and goofy at the same time.

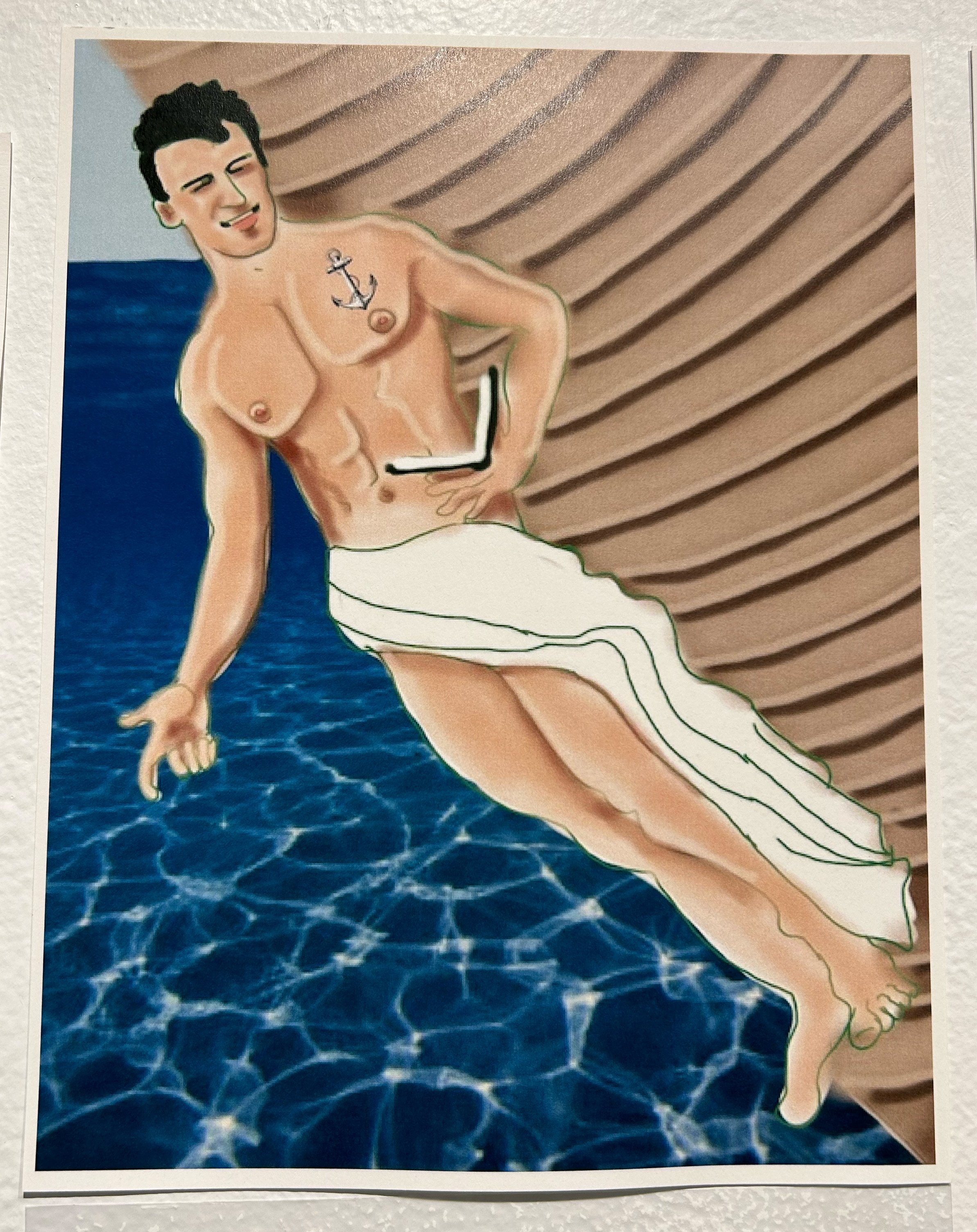

The Boy

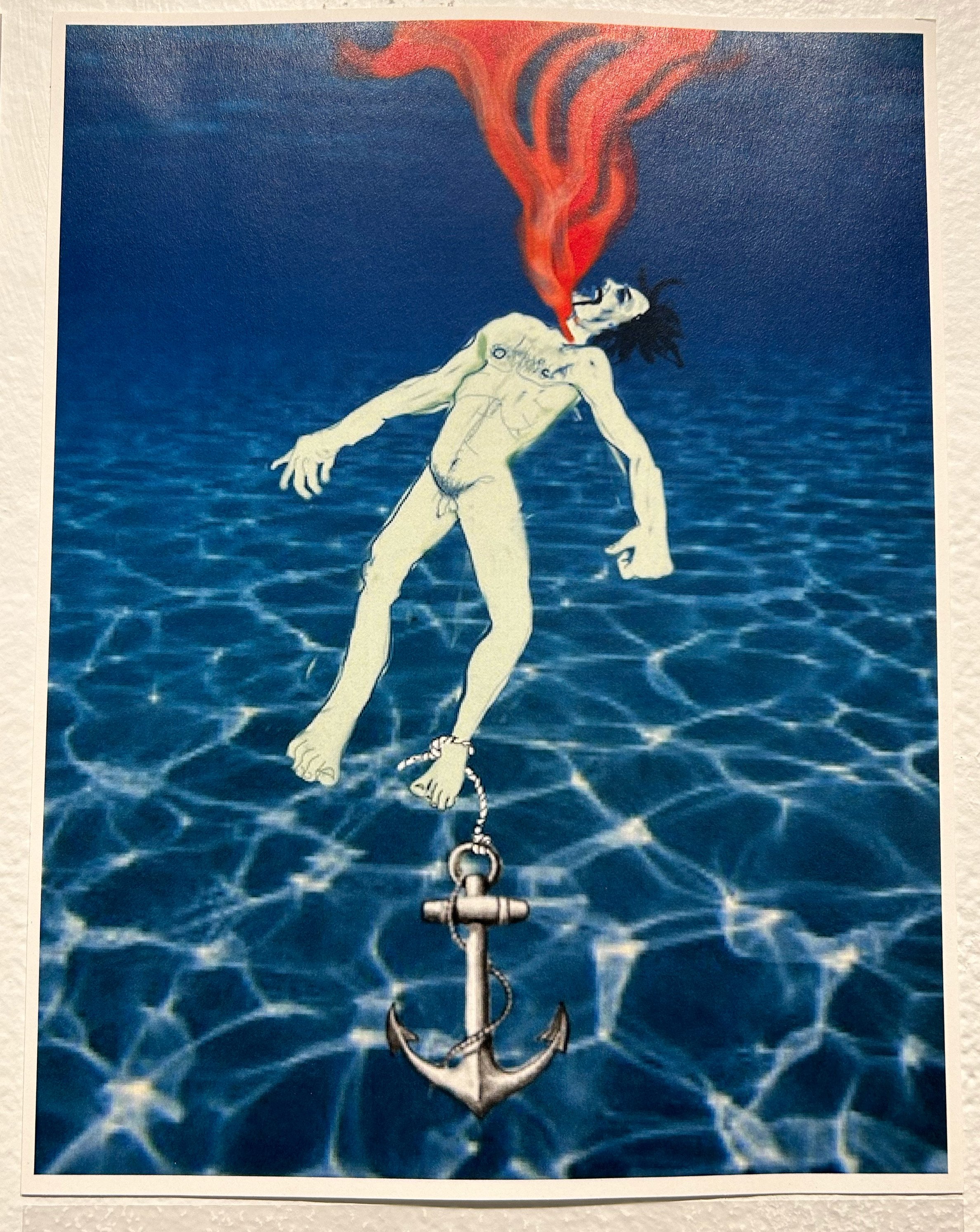

The boy was not as young as he appeared. His smooth skin and round cheeks made him look no more than sixteen, but in fact he was twenty. The crew appraised him as he came aboard the ship in Boston. They looked at his thin wrists, ankles, and neck and doubted he could do his share. “Better a cabin boy, than a sailor,” they thought. For some the notion of buggering him came forthrightly to mind. In addition to his sea bag, the boy carried a fine leather box with brass fittings. It contained his beloved squeezebox. “Well,” thought the crew. “If he can’t haul the anchor at least we’ll get a jig out of him.”

That night with the coast still in sight and the moon rising full on the horizon, the crew had a party. The one-eyed fiddler, The Moor on guitar, and the boy and his squeezebox provided music. Several of the men sang. There was some vigorous dancing, but all preferred the ballads of lost love. The finest voice belonged to a sailor named Young Matty. He sang the last song before all turned in for the night.

I leave my heart wi thee my love

Tho forc’d from thee to stray

Wi tear stained grief I onward move

And lonely make my way.

How tedious will the hours appear

Each day a year to me

For ah! my love, my only dear,

I leave my heart wi thee.

Every man thought about what he was leaving behind and what lay ahead. It might be as much as a year before they saw home again.

The Boy realized he’d never played with a musician as fine as The Moor. The notes from the guitar flowed like water under, over, and in between the traditional melodies he and the fiddler knew. Later, below decks in his hammock, he fell asleep and dreamed about black fingers dancing above ivory inlays, touching down on brass frets.

For as much as a fortnight The Boy did well enough. He was as agile as a monkey and showed no fear. He had surprising stamina. He could keep pace with the hardest working of his mates from dawn to dusk. However, it was clear to all that what he lacked was strength in his arms and shoulders and back. The crew accommodated him without resentment because he was modest and quiet. He said little beyond a mumbled, “No, sir. Yes, sir,” but he smiled readily. His nightly music enchanted his shipmates and inclined them to lend a hand when he needed it.

Then it all came to an end. There came a blow, not even a storm just a good strong blow. The boy and four others were high up the mast, taking in the sails. He lost his grip and fell. That should have been the end of him, but his foot tangled in a rope and he swung into the sail. In desperation, he grabbed whatever he could get a hold on. The canvas gave way at a mended spot and began to tear. The boy road the rip to within ten feet of the deck, snapped loose, and landed on his back. He lay there with the wind knocked out of him, but no bone broken and hardly a bruise. All around him there was chaos as the able bodied men scrambled to save the flapping, tattered sail and control the ship as it rocked in the wind. The captain fought the wheel and shouted orders. The boy struggled to his feet still having trouble breathing and then vomited over the rail. The Moor grabbed him around the waist out of fear that he’d go over board and yelled in his face, “Just get out of the way, boy. We’ll deal with you later.”

When order was restored, attention turned to the boy. No one had any taste for it, but a flogging was clearly in order. His shipmates dreaded what was to come, especially those who had felt the lash, but his error was too grave to ignore. The captain signaled the Moor to proceed. The black man laid his beautiful hands on the boys shoulders and said, “Take off your shirt, boy.” The boy knew the jig was up, but he shook his head, “No.” The Moor said, “As you wish.”

He was tied to the mast and the Moor grasped the back of his shirt and ripped it open. In the tight quarters of the ship there was little privacy and modesty was non-existent. However, in that moment, many of the crew realized they had never seen the boy without his shirt. For the first time they glimpsed where his thin neck met his narrow shoulders and they saw his delicate shoulder blades. They also saw that his chest, just above the rib cage, was wrapped tightly in a gauzy, white band of fabric.

The Moor understood the situation before the others. He stood behind the boy, blocking him from view and said over his shoulder, “Captain, if you would, please step forward.” The Moor could not deny that he was amused and aroused.

The Captain also quickly understood the situation, “Sweet Jesus!” he muttered.

The boy looked over her shoulder into the Captain’s eyes. There was a shift in her voice and manner. All pretenses were dropped.

“Captain,” the boy said. “As you can see, I’m no seaman, but if you spare me the lash, I assure you this will be a voyage you won’t soon forget.” The boy stated this with a confidence she had never shown as a deck hand.

The Captain looked like a captain. He was handsome and vigorous. He came from a wealthy family and had grown even wealthier during his decade at sea. He was an exceptional businessman. His trips were profitable to a degree that others viewed with suspicion, especially since he never dealt in slaves. He had the loyalty of his men because he fed them well, paid them generously, and treated them fairly. And yet, he knew, and they knew, he was not a natural leader of men. He often didn’t know what his crew wanted or expected from him. There was no ease between them. He sensed that the boy had created a crisis in which he had much at stake, but he hadn’t a clue how to resolve it. As he often did at such times, he relied on the Moor. He looked up at the black man questioningly. With a wide grin, the Moor yelled, “Take her to the Captain’s quarters. We’ll get to the bottom of this in private.” Had the Moor stressed the words “bottom” and “private? Would his facial expression best be characterized as a grin or a leer? Whatever the case, the crew was left on deck feeling relieved and giddy. It seemed their young mate would be spared the lash, that he was not a mate at all, that he was a she, and that the routine of their working lives had been broken by a most entertaining series of events; events that they’d be telling stories about for years to come.

Balance and routine were quickly restored. The Captain had no taste for drama and he had the advise of The Moor to rely on. The Boy became the cook. Since the cook couldn’t cook and was a better seaman than The Boy, this arrangement pleased everyone. Rather nice quarters were constructed for The Boy in a storage locker off the kitchen. Included were a rope strung bed frame big enough to accommodate The Boy and The Captain when he visited. His visits to the room off the kitchen were occasional and in his own quarters, on many a night, he continued to teach Young Matty to read. The Moor made it known that The Captain had proprietary rights to The Boy. She was working off the debt she had incurred as a stowaway, but the debt was only owed to The Captain. None questioned the correctness of these arrangements. The food improved. The Boy, The Moor, The One Eyed Fiddler, and Young Matty entertained the crew more evenings than not. Young Matty could read many passages of The New Testament with few prompts. He studied hard. Often he didn’t emerge from The Captain’s Cabin until dawn. The Boy enjoyed her times with The Captain. His visits occurred once or twice a week and were vigorous and enthusiastic, if brief and a bit impersonal. The Boy was no stranger to whoring and this was easy work. She slept well those nights, dreaming of beautiful black hands. In her dreams, The Moor’s hands no longer attended to his guitar. Rather they touched her white body, gliding over smooth skin, grasping handfuls of soft flesh, slipping out of sight.

One night The Captain fell asleep in The Boys bed. Two hours later he awoke hot and sweaty with fever. He swung his feet over the edge of the bed, intending to dress and go back to his quarters, but he was too sick to rise.

“Lay back down and get under the covers,” The Boy said. The Captain fell back against the pillow. The Boy pressed against his back to warm him and pulled the wool blankets over the two of them. The Captain sweated and shivered in her bed for three nights. She gave him water and tea and soup when he was able to eat. At times he seemed hardly conscious even if his eyes were open. During one of these spells he became aroused and moved to cover the boy. She accepted him. He radiated heat from his fever and his movements were slow and unfocused as though they were making love in a dream. It had been a long time since the boy had found the body of a man so pleasurable.

When the fever broke and The Captain slowly regained his strength and vigor, they began to talk to each other. This is part of what they said:

The Captain: I’ve never dealt in Africans, but my family has. I’ll take no part in making a man a slave. I think slavery is a temptation from God; a test that will show us what price we put on our souls.

The Boy: I came aboard your ship because there was a man who meant to do me harm. He reckoned he owned me. He said if I didn’t do as I was told he’d kill me, but the things he told me to do were killing me.

The Captain: I’m the third son. My oldest brother has the business. The next went into the clergy. They sent me to sea in this ship when I was fifteen. When my father died, it became mine. Now I’ve sailed it as captain for ten years.

The Boy: I would have played my squeezebox and served beer in the saloons, but the man told me I had to pay my way. By which he meant I had to pay both of our ways. There was nothing I could say no to if the price was right.

The Captain: My brother can’t abide me because my voyages are more profitable than his. You will think it is gold or rum or molasses or any of the other things I trade in that makes the money, but it is tea. Tea, of all things, has made me rich. I’m done with sailing. I’ll be a businessman in Boston.

The Boy: The Moor says I’m a fine musician. I’ve never heard anyone who played better than him. When we play together I feel I’m good too.

The Captain: Maggie, you need not receive me here in your room. I’ll not force you or hold your passage over your head.

The Boy: I’m not doing anything I don’t want to do, Will.

The Captain: Can I have a song then?

The Boy:

Sometimes I'm up, and sometimes I'm down,

(Coming for to carry me home)

But still my soul feels heavenly bound.

(Coming for to carry me home)

If I get there before you do,

(Coming for to carry me home)

I'll cut a hole and pull you through.

(Coming for to carry me home)

If you get there before I do,

(Coming for to carry me home)

Tell all my friends I'm coming too.

(Coming for to carry me home)

As Young Matty mastered bible verses he would read them aloud to his shipmates as they sat and smoked a pipe when the day’s work was done. They marveled at both his literacy and the stories. One evening off the coast of Spain, he read one of his favorites:

Immediately Jesus made the disciples get into the boat and go on ahead of him to the other side... Later that night, he was there alone, and the boat was already a considerable distance from land, buffeted by the waves because the wind was against it.

Shortly before dawn Jesus went out to them, walking on the lake. When the disciples saw him walking on the lake, they were terrified. “It’s a ghost,” they said, and cried out in fear.

But Jesus immediately said to them: “Take courage! It is I. Don’t be afraid.”

“Lord, if it’s you,” Peter replied, “tell me to come to you on the water.”

“Come,” he said.

Then Peter got down out of the boat, walked on the water and came toward Jesus. But when he saw the wind, he was afraid and, beginning to sink, cried out, “Lord, save me!”

Immediately Jesus reached out his hand and caught him. “You of little faith,” he said, “why did you doubt?”

That night Young Matty dreamed he had become the masthead of the ship. As is possible in dreams, he was carved from wood and, at the same time, he was his own familiar flesh. His feet skimmed across the tops of the waves and against his back the bow of the boat pushed him forward with all the power of the wind in its sails. He knew The Captain steered the ship and he felt deep faith in The Captain. Young Matty, as the masthead, held a bible open in his hand and even in the rush of wind and waves he kept his eyes on its pages and sounded out new words.

In the ship’s hold were many bolts of fine fabric. The Captain had told The Boy to take as much yardage as she wanted. She had sewn herself dresses, skirts, and blouses of simple designs that contrasted with the richly patterned and brightly colored cloth. Many of the men thought she looked like a gypsy, especially when she played her squeezebox. She made herself as pretty as she could and walked along the deck, past Young Matty reading the bible to a circle of sailors, and made her way to The Captain’s quarters. It was quite rare that she would seek him out. She knocked on his door and said, “Will, I don’t want to disturb you, but could we have a word.”

“Please come in, Maggie,” he replied.

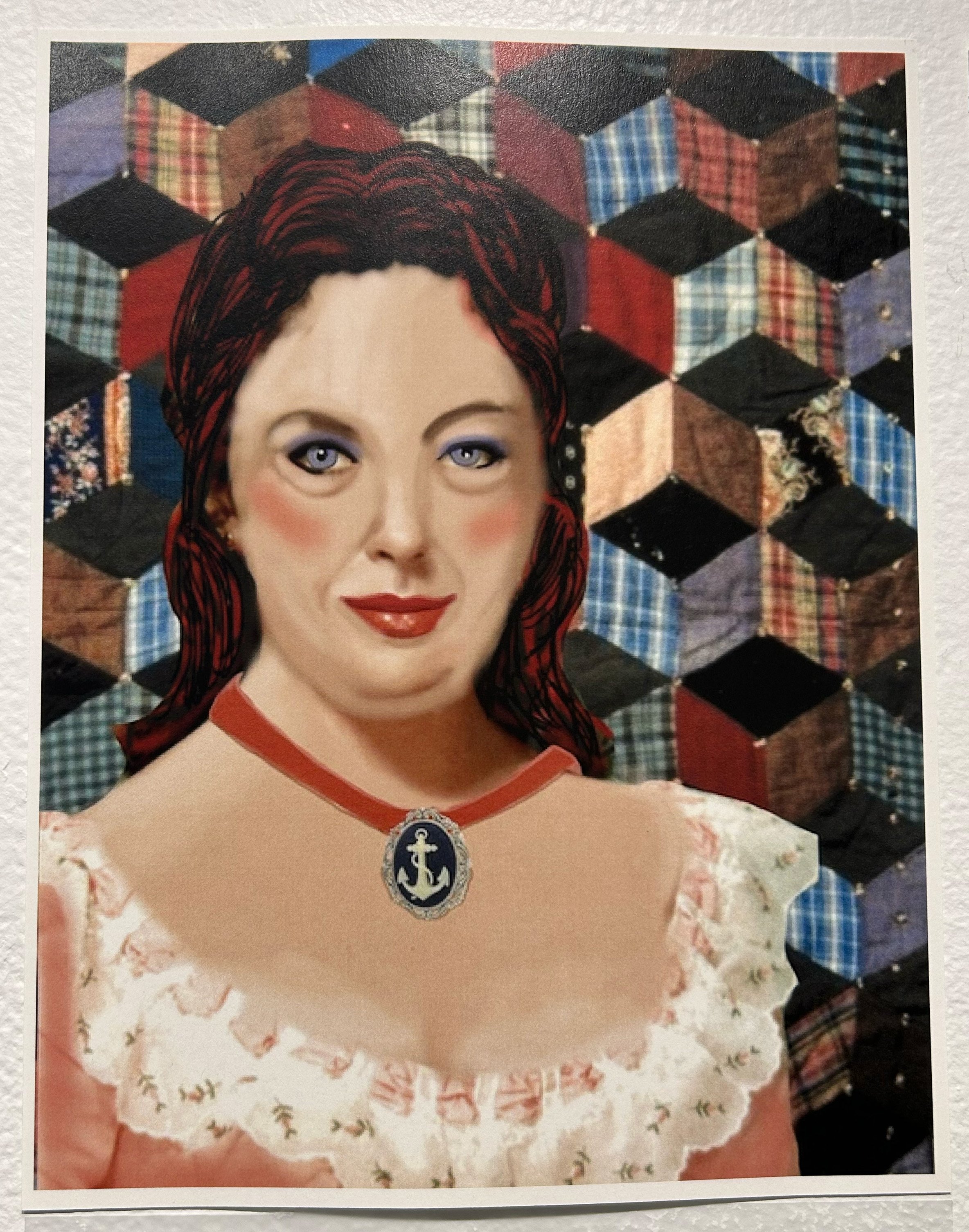

She stepped in and looked around the room. She saw a whole shelf of books, a chess set in mid game, a fine telescope and other brass instruments, a writing desk with logs, account books, and journals. The Captain’s bed was covered with a quilt of a design she had seen her Mom sew; tumbling blocks it was called and the contrast of light and dark fabric made it look three dimensional.

“What is it, Maggie?”

“I’m not sure where… how to begin.” He waited. “Will, I’m going to have a child… a baby I mean.” She began to weep. He said nothing and she cried harder. He approached her.

“This comes as a surprise,” he said.

She said, “I know what I am and what I am to you. I don’t want anything… anything more from you, but I thought you should know and I want to go home. I want to go to my Mom to have my child. She is a midwife. If I’m not with her, I will be too afraid. When we’ve crossed back will you take me to Providence.”

“But you’ve told me it isn’t safe for you in Providence.”

“The Moor says he will take care of it.”

“Did you tell him you were pregnant?”

“No, but I told him I wanted to see my Mom and I told him what the man had threatened me with and he said he would fix it so I had nothing to fear.”

“Well, if he says he will, he will.”

There was a long silence and then The Boy turned and left. Quite late that night, long after she had fallen asleep, the boy felt her bed shift as The Captain lay down next to her. She held up the cover and felt the heat of his skin against her body. Usually, when The Captain came to her in the night no words were spoken, but this night, he delivered a speech that had perhaps been taking shape in his mind the whole evening or perhaps he’d been thinking it over even longer.

“Maggie, I’m a peculiar man and there is a kind of affection I don’t have in me. I intend this to be my last voyage. I’ll be a businessman in Boston and The Moor will captain my ship. In my new life, I’ll need a wife to keep my house and raise a family and see to certain social demands of the community. Since the family is now begun, I want you for my wife. I will provide for you and respect you. This child and any others that come along will grow up in prosperity. The attention and pleasure you have provided me on this voyage have been more important to me than perhaps you realize. As we have been to each other these last months, I would hope we could continue to be for a long time to come.”

The Boy had long ago stopped believing that her life would be guided by love or romance or passion and she could recognize a good deal when one was laid before her. “Yes” she said, “I shall be your wife, but I must go to my Mom and have my child in her care. I’ll join you in Boston as soon as I can travel.”

Three months later, they were married in Newport and then the ship sailed up the bay to Providence. As The Boy was going ashore, with a large sum of money in her purse, The Captain said to her, “Maggie, you will be coming to me won’t you?”

“Yes, I’ll be coming to you, Will,” she replied. Then she handed him the fine leather box with the brass fittings that contained her squeezebox. “Keep this safe for me.”

“Well! Look what the cat dragged in!” Mom shouted. “And looking mighty fine, too. And my goodness with a bun in the oven!” Mom was a whore and a midwife to whores. It was often said she had once been the best-looking woman in Providence. However, she was quite fond of food and booze and opium, so her legendary career was much diminished. Still she was better off than many an old whore. She had a little house along the river, not far from the docks. A policeman, a former governor, and a minister still visited her. They had many a fond memory of her from the old days and saw to her safety and comfort. As she looked at her daughter, the elation she had felt when The Boy first appeared evaporated.

“Oh, but darlin’, what’ll happen when he hears you’re about?”

“Its been taken care of.”

“But…”

“There’s nothing to fear, Mom.”

Late into the evening they sat together warming their feet before the fireplace. They sipped tea. Mom had laced hers with rum.

“Maggie, my love,” Mom said. “Why are you here, dear?”

“Isn’t it obvious? To have my baby.”

Mom sipped from her cup. ‘No, child. Not at all obvious. Why aren’t you with your husband, in his fine house, in the care of a good doctor?”

The boy stared into the fire for a few long minutes. When she spoke to her mother again it was in a calm, confident voice.

“Well, you see, Mom, I cannot be sure whether my baby will be white or black and I didn’t want to receive the answer to that question in the presence of my husband.”

“Ah, my girl. You’ve gotten yourself into a fix, haven’t you.”

“I’ve been in worse, Mom.”

The older woman loved her daughter, but, like many a mother and daughter, over the years, they had been a great disappointment to each other. Perhaps, Mom thought, now we’ll all get a new start.

“And if the baby is black, my dear, what will you do?”

“There’s no shortage on this waterfront of girls who would be happy to have their white baby raised by a wealthy family in Boston.”

“Ah, Maggie. And so we get to the real reason you’re here. You know full well any such girl would have found her way to me.”

The Boy looked at her mother over the rim of her teacup. The rim was gold and just below it the cup was encircled by a garland of tiny, blue, painted flowers.

“Do you know any such girls, Mom?” The boy asked.

“A few, my dear. A few.”

The Boy’s breasts got huge and her milk flooded in. She thought, I never could have passed myself off as a boy with these tits. She mastered feeding both The Twins at the same time, their tiny swaddled bodies crisscrossed in her arms, a greedy mouth sucking with surprising force on each of her nipples.

The twins were less than a month old when The Boy and Mom disembarked from the little steamer that had brought them to Boston from Providence. Each carried a wicker basket holding a baby. The Captain was there to pick them up in a carriage.

“Maggie,” he said. “What have we here.”

“Our sons, Will. The Twins.”

He looked into the baskets at the two faces deep in sleep. Each of the infants was wrapped in a quilt of a design he knew well. When he had first gone to sea, his mother had sent him off with a warm quilt of this same pattern. “I see one of our sons is of dark complexion, Maggie.”

“Indeed he is, but he is no less ours for his blackness. His mother came to Mom for care. She was a freed woman, not a slave, but totally alone in the world. The birth was terrible.” The Boy got tears in her eyes and her voice quavered. “The black girl made me promise to take care of the baby… then she was… gone. I put the baby to my breast when he was less than an hour old. Since then, he has been as much mine… ours… as his brother.”

The Captain extended his index finger to his black son who grasped it without hesitation.

It was only a ride of fifteen minutes from the dock to the house The Captain had bought as a home for his new family. The carriage passed through a gate and up a circular drive. It stopped in front of a large white wooden house. At the very top of the house’s roof was a small porch surrounded by an iron railing. From there, The Boy thought you could see the harbor and await the arrival of a ship, but he’ll be here already. There’ll be no one I’m waiting for. Then she saw that Young Matty stood in the door way of the house smiling broadly as they all arrived.

In response to The Boy’s quizzical look, The Captain said, “This is Young Matty’s home, too. I have made him my ward. I’ll see to his education and a ship is being built that he’ll captain when he is ready. He has quarters above the carriage house. There are also rooms there for The Moor. He will be part of our household, as well, when he is not at sea.”

That night The Boy was reunited with her squeezebox and she sang a song for them:

Well go down yonder Gabriel

Put your foot on the land and sea

But don’t you blow that trumpet until you hear from me

Well look way over yonder

See people dressed in white

I know it was God's people I seen 'em doin right

Oh look way over Jordan

What do you think I see

I see a band of angels and they’re comin’ after me

Well meet me Jesus meet me

Meet me in the middle of the air

And if these wings should fail lend me another pair

As they had been to each other those months on the ship, they continue to be for a long time.

In the summer of 2013, I met a woman named Joke Bijl-Costerus. She was a sailor and played the accordion. She sang a Dutch song about a girl who goes to sea disguised as a boy. That was the beginning of The Boy.

John Kotula

An exaggerated story: a story that is so strange or surprising that it seems very unlikely to be true.

Sometimes in the form of “the one that got away”; something desirable that has eluded capture. This phrase comes from the angler's traditional way of relating the story of a large fish that has managed to escape after almost being caught. It can also refer to a romantic relationship.

You are invited to write or draw a “fish story” in the sketchbook… or a fish poem… or a fish lyric… or a fish joke… anything fishy.

Take a fish sticker to thank you for your participation!

Copies of the booklet “Coming Out” are available free at the gallery

Jim Luken is my friend and frequent collaborator; see our PechaKucha presentations.

We share the same birthday, May 14th. He is a year older than me. He’ll hit 80 in 2024, me not until 2025. For the last two years we have thrown joint birthday parties. Next year I’ll have to low key being a mere 79 and make sure his milestone gets most of the attention. He told me he was born on Mother’s Day. I said, “Oh! Me too!” He said, “No you weren’t. Mother’s Day couldn’t fall on the same date two year in a row.” We checked and he was right. My mother was not a person who would let facts stand in the way of a good story. At some point, she decided that she liked the idea of me being born on Mother’s Day instead of almost being born on Mother’s day so that’s the information I grew up with.

Over the last year, I’ve followed the creation of Swan Song closely. I was honored when he asked me to design the cover. It is a great culmination of Jim’s significant and varied career as a writer.

Swan Song

is available on Amazon.

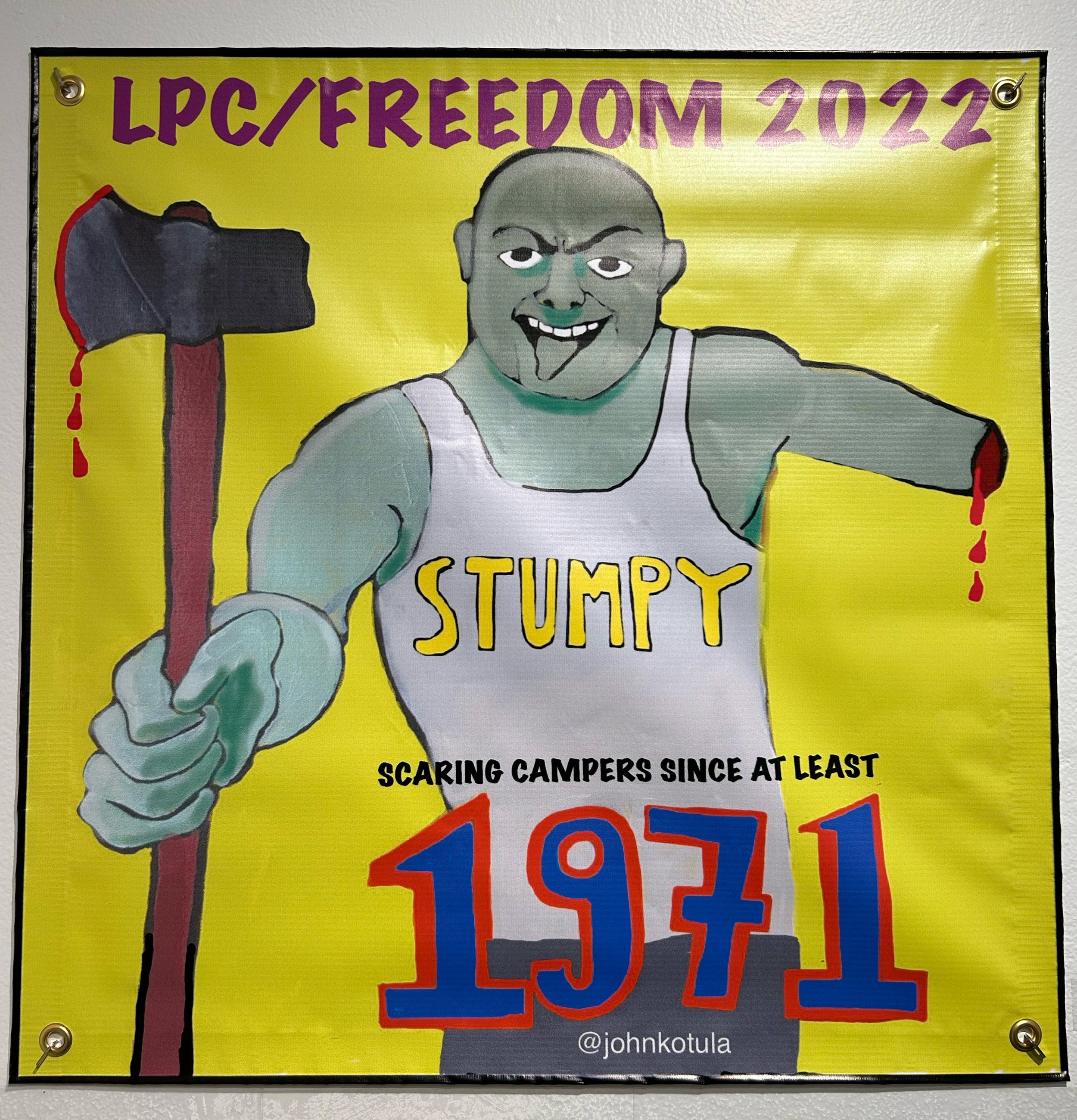

The Luethi-Peterson Camp in Freedom, New Hampshire has met for decades in a big, old farm house. In the dining room there is a frieze of paintings, one for every year, that tells the history of the camp. The one for 1971, which was painted by my wife Debby Drew, depicts the legendary Stumpy, a one armed, maniacal psycho killer, whose story has been scaring campers for at least half a century and probably much longer. There are, no doubt, many versions of Stumpy’s tale, told and retold in many camps. Here, in synopsis, is the one that raises campfire goose bumps at LPC/Freedom.

In the Spring, a young man arrived in the area from his family farm near Boston. He road a nice looking horse and led a sturdy mule that was loaded with provisions and tools. Against all advise, he’d come to homestead in New Hampshire. He’d been warned that the winters were long and brutal. He worked hard and by fall had built himself a one room cabin, a stable and a root cellar. He trapped some beaver and swapped the furs for flower, sugar, coffee and a bit of whiskey. When September arrived he focused on chopping wood to keep himself warm in the winter and created a pile he was sure would last him till spring. It didn’t. The first snow fell on October 1st and it snowed and snowed and snowed. It was the worst winter anyone could remember. The pond froze solid by October 15th and never thawed until May 1st. By February, the young man knew he was in trouble. His whole world consisted of snow, ice, cold, and hunger. He thought about trying to ride his horse or mule to town, but that was a two day trip and from the look of the animals they’d never make it. He thought that before long he’d know what horse and mule tasted like. Undeniably, he needed more wood. He sharpened his axe and made his way to the edge of the woods slipping and sliding on the ice. He took a good swing at a tree on the edge of his clearing. The axe didn’t leave a mark on the tree. It bounced back and he realized the tree was frozen through. The only thing he could think to do was swing harder, so he gave it all he had. This time the axe flew out of his hands. The handle hit his head knocking him unconscious. When he came to and sat up he realized that his head was not the only thing the axe had hit. It had also severed his left arm just above his elbow and blood was spurting from the stump. The young man was simultaneously bleeding to death and freezing to death. He lost his mind. In that moment, he crossed over into a new dimension, neither alive nor dead, he entered the realm of ghosts and myths and legends. He became Stumpy, the one armed psycho killer.

Over the years, town folks, farmers and hunters reported regular sightings of a one armed man carrying an axe. There were some close calls and some narrow escapes, but more seriously, with some regularity, people vanished. They would take a solitary walk in the woods or a moonlight swim in the pond and never be seen again. That is why, campers, you should never wander off into the woods by yourself and why you should never think of sneaking out at night to walk in the moonlight.

How Art Made The World Safe from Stumpy.

This year, I spent a week at LPC/Freedom as artist in residence. I worked with campers to create a large mural (10 feet X 8 feet) on canvas mounted on the barn door. In one discussion, a counselor suggested that if one of the painting from the dinning room frieze were painted into the mural that would be a way of including some of the camp’s history. I liked this idea and talked to the campers about which painting should be included. Stumpy from 1971 was the unanimous choice. That day, after lunch, I made an announcement. I said, “Look, I just wanted you to know that Stumpy is in the area. He has been sighted.” There were giggles. I continued, “Please, take this seriously. Don’t wander off by yourself and be careful if you’re walking by the edge of the woods. You’ve been warned.” The mural was completed and it did include a representation of Stumpy. On my last day, a time was scheduled to discuss the mural. I started off the discussion by telling this Story:

John The Artist tried to warn the camp that Stumpy had been seen in the area, but he could tell that they weren’t taking him seriously. He said to himself, “Well… I tried to warn them. I guess that’s all I can do,” and he got in his car and drove to his hotel for the night. However, all the way to North Conway he was worried. When he got into bed he couldn’t sleep. He kept thinking, “Maybe a warning wasn’t enough. Maybe I need to do more. What if Stumpy gets my beloved wife or my beloved granddaughter? What if he gets one of the wonderful campers I met this week?” John The Artist decided he needed to do more, so he got out of bed, got in his car and drove back to Freedom. He parked near the dumpsters. As soon as he step out of the car, he was hit with great force in the back of the head and fell to the ground unconscious. When he came to, Stumpy was straddling his body with his axe waving wildly above his head. Stumpy screeched, “Ha, ha, ha! I’m going to chop you!” “No! Stumpy! No!”, John the Artist shouted. “Why shouldn’t I?” asked Stumpy. John the Artist had no idea what to say. He was just stalling for time, but he opened his mouth and these words came out: “Look! I can make you famous! I am a famous artist.” (This was a lie. John the Artist was a good artist, but not a famous one.) He continued, “I’ll paint you into the mural I’m doing up in the barn. When it is finished, people will stop to take selfies with your picture. They’ll put them on Instagram and TikTok. You can have your own Instagram and TikTok! You’ll go viral! Eventually, you’ll have your own reality TV show.” Stumpy considered all this and said, “OK! Let’s try it, but remember, Ha, ha, ha, I can chop you whenever I want.”

Still without a real plan, just stalling and hoping for a miracle, John the Artist led Stumpy to the barn and posed him in front of the mural. He took a piece of charcoal and the first thing he drew was Stumpy’s axe. Something amazing and inexplicable happened! When the axe was on the canvas as part of the mural, it disappeared in the real world. It just faded away! Next John the Artist, drew Stumpy’s arm. The same thing happened. It stopped existing there in the barn attached to Stumpy’s body and existed only in the mural. Quickly, John the Artist drew the rest of Stumpy’s body. Stumpy was reduced to just a head floating in the air. The head cried out, “What have you done to me?” John the Artist replied, “I’m not… I’m not really sure. I think you are leaving the real world and are becoming just a work of art. I think you only exist as an image on canvas. Stumpy, I don’t think you can hurt anybody anymore.” He started, drawing the head and as it began to fade away, Stumpy looked into his eyes and said, “Thank you.” And that’s the story of how art made the world safe from Stumpy.

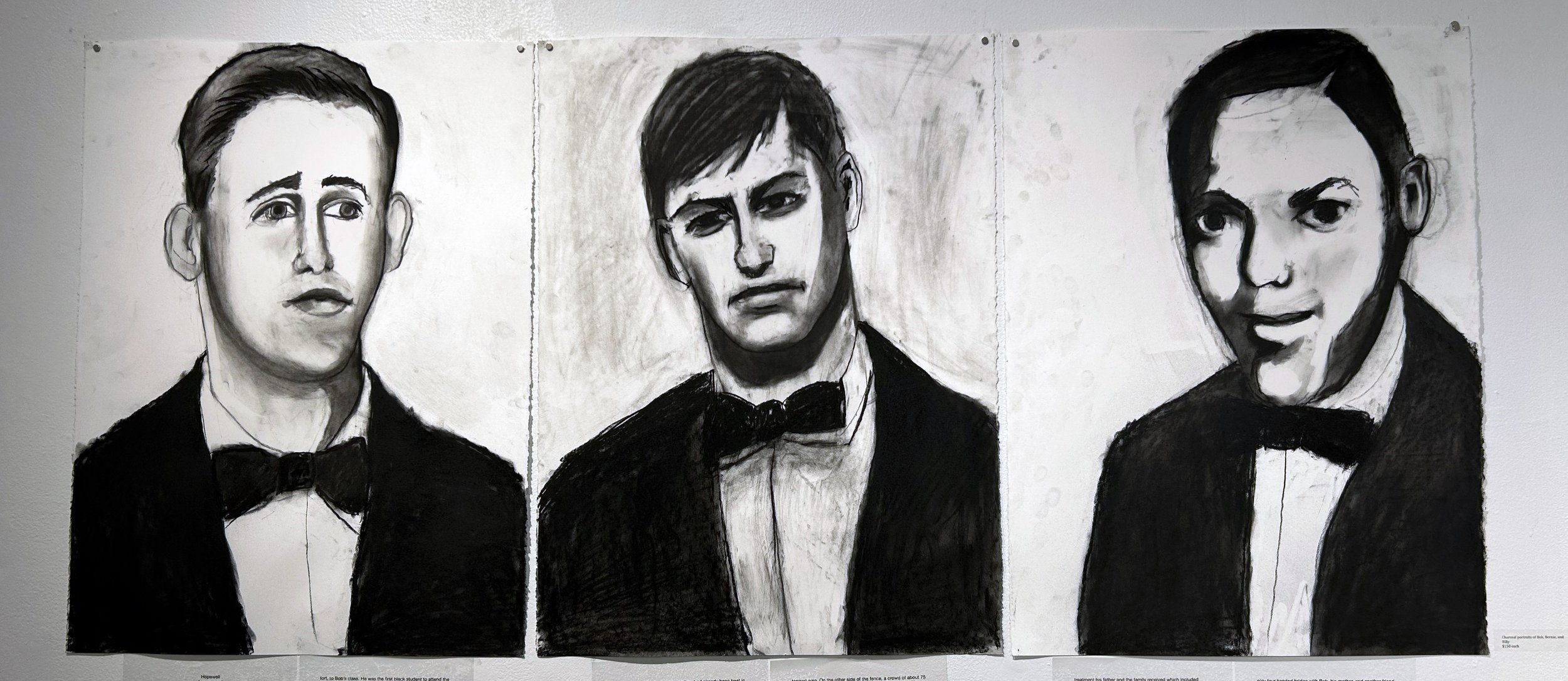

Hopewell

A couple of years ago, my friend Bob Poole told me about some events that occurred during his senior year of high school in Hopewell, Virginia. I have known Bob for over forty years and as far as I can remember this was the first time he told me these stories. They have lodged in my thinking, like scenes from a powerful movie or book. His stories seem informative to me about racism in the early sixties. I have the idea that if I can fully understand what happened to him, I’ll learn something important. Bob and I have collaborated to try to gather as much information as possible. I made a trip to Hopewell during which I visited local historic sites. I’ve interviewed people who knew Bob in high school. Still I feel this material is illusive and that my writing about it is in progress. Perhaps what I’m sharing here will be part of a longer piece.

Bob’s school was desegregated without much fan fair during his sophomore year. The first year, 8 honor students from the black high School, Carter Woodson High School, were enrolled at Hopewell High School. The second year a larger group of black students came over. Among them was a boy named Burnie Epps. He and Bob were both basketball players and they started to hang out together. Bob says, “I was a friendly guy interested in knowing a black guy.” Burnie’s father was the principal of the Black High School. A few years later the town built a new high school and consolidated the white and black schools. Mr. Epps became the principal of the fully integrated high school.

Bob had previously had a black buddy in sixth grade. He was attending a catholic school and some of the military kids from Fort Lee were students there. The nuns announced that they would be admitting Daryl Johnson, a negro student from the fort, to Bob’s class. He was the first black student to attend the school. Bob says, “We really hit it off. We were friends all year, but the next year he left. It broke my heart.”

In about February of Bob’s senior year in high school there was a basketball game against Hopewell’s traditional rival, Petersburg. The two teams played each other twice a season and this would have been the second game. It was played at Petersburg, about five miles from Hopewell. The first game, which Bob is pretty sure they lost, would have been played at home. The rivalry between the two towns was intense. Brawls often broke out under the stands at football games. Technically both schools were integrated, but Petersburg had a much higher percentage of black students than Hopewell. Both the junior varsity team, on which Burnie played, and the varsity team took the bus to Petersburg. Bob doesn’t have much memory of the junior varsity game. However, for the game played by the older guys the stakes were high and the rivalry even more tense than usual.

Bob’s friend Billy Derski was the center for their team. He was about 6’ 3” and Bob describes him as a low key, shy, shuffling kind of guy; a really nice kid. His family was known around town as The Beverly Hillbillies because they had sold farm land and moved into town with enough money to build a big house and for Billy to drive a yellow Corvette. His mother drove a Cadillac. Mrs. Derski was looked down on around Hopewell. She dressed like she was still on the farm, was often barefoot, and was known to be a profane loudmouth. Billy’s father, Stan, was well liked and looked up to as the catcher for the local fast-pitch softball team, the only entertainment in Hopewell besides high school sports. Bob and Billy were good enough friends that they double dated. They’d barrow the Cadillac, pick up their girlfriends, and go parking. With Billy and his date in the front seat and Bob and his in the back, they’d steam up the windows.

From the first jump the game was physical and aggressive. Bob can’t remember exactly what was at stake but it might have

been moving on to finals, besides they had already been beat in their first game. There was a black kid playing center for the other team and he was a better athlete than Billy. However, Billy was a worker and wasn’t conceding anything. Bob was on the bench when Mrs. Derski, began yelling loud enough to be heard by everyone in the gym, “Hit him, Billy!” However, she didn’t say “him”. She yelled the “n” word. Bob and the players on the bench looked at each other in amazement. Certainly they had heard the “n” word thrown around plenty, but not this overtly, not so publicly. Bob says one of his strongest emotions was was a kind of excited curiosity, “Holy shit! What in the hell is going on here? What is going to happen next?” After Mrs. Derski had yelled the racial taunt five or six times, Billy in fact slugged the other player and triggered a melee on the court. According to Bob, this was very out of character. He wasn’t like that at all. (As I try to understand the scene, I’m guessing that it was the only way Billy could think of to get his mother to shut up and end the humiliation. This was not the first time she had embarrassed him in public.)

The coaches and referees broke up the fight, talked to the boys, made them shake hands, and the game went on. Bob, who spent a lot of time around high school sports in that era, said that the basic understanding was that “boys will be boys”, meaning that they were naturally dumb, didn’t have any impulse control, and loved to fight. Hopewell lost the game. End of story? Not really.

The boys went to the locker room and got into their street clothes to get on the bus and drive the five miles home. A couple of sheriffs arrived and pulled the coaches, refs and bus driver aside. They talked in low voices. Then they assembled the boys and said, “This is how it’s going to go, we are going to wait awhile longer. We’ll tell you when its time to leave, then you’re going to walk out quickly and get on the bus as fast as you can. No horsing around. Get on the bus, sit down and shut up.” When the boys went through the locker room doors they found their bus parked very close to the exit in a large fenced in black topped area. On the other side of the fence, a crowd of about 75 black men and boys were gathered. The exit was narrow. The school bus had to slow way down passing through the gate. At that point, something heavy, maybe a brick, hit the bus. The crowd was loud and threatening. Once he had cleared the gate, instead of driving away, the bus driver, threw it in reverse and chased and dispersed the crowd going backwards. The players were all scared according to Bob, but his black friend, Burnie, who was sitting right behind him, got on the floor under the seat. Somebody said something to Burnie along the lines of, “What are you worried about?” But Burnie said, “If they get on this bus, what they do to me is going to be worse than what they do to you.” Finally, the bus driver drove away leaving the crowd behind them.

This incident was never mentioned again by coaches or school officials. As far as Bob can remember parents were unaware of it or didn’t think it was a big deal.

It is not lost on me that in this incident Black people were aggressive toward white people. Of course, in the history of racism, it is white people who have victimized Black people not the other way around.

I say to Bob, “I would have been scared driving home weren’t you afraid they would have come after you.” He says, “Nah, nothing like that would have happened. This was Virginia, not Alabama.” It is my impression that during our talks Bob had a tendency to down play the racial violence he had heard about and experienced growing up in Hopewell. He acknowledged that the clan had a presence in town and that cross burnings were not uncommon. One summer during college he returned home and worked in a chemical factory. One of his co-workers was a young black man named Curtis Harris Jr. whose father was a local civil rights leader. Curtis Jr. was one of the first black students to integrate Hopewell High School and his father was instrumental in pushing for integration of the school. He told Bob about the

treatment his father and the family received which included physical confrontations by the clan, bricks thrown through their windows, attempted fire bombing of their home, and the father being thrown in jail several times for organizing and civil disobedience. The Reverend Curtis Harris, Sr. and Martin Luther King were friends and coworkers on many projects. King was frequently in the Curtis home, but he always arrived at night and his visits were secretive. Reverend Curtis’ history turned out to be inspirational. In 1998 he became the first black mayor of Hopewell. Major public buildings in Hopewell are named after him. He died in 2017 at the age of 93.

Not long after this incident, Bob invited Burnie over to his house to watch a basketball game. He said, “My dad had worked on the antenna on the roof and we had pretty good reception.” Burnie was also pals with Bob’s next door neighbor, Mike, and Mike was invited, too. After school, Bob’s mother met him at the door looking really distraught. She said, “Bobby, I’m shocked. Your brother told me you invited Burnie to our home to watch the game. Your father is coming home early to talk to you about it.” Bob was taken aback by this. In his house it was clear that black people were to be treated in a friendly manner. His mother often sat and chatted over coffee with the women of color who worked for her. The “n” word was forbidden and “rednecks” and “hillbillies” were disdained. However, it was a working class neighborhood and the families in several nearby houses would have fallen into those categories. Bob’s dad said to him, “You’re going to graduate in June and leave town, but we have to live here. This could make problems for us. Burnie can come and watch the game tonight, but not after that.” Bob didn’t argue. He thought his Dad was right. He was leaving and at college he could do whatever the hell he wanted.

Right at this point in the story, there is a mystery, some information is missing that is needed to explain what happens next. In June, Burnie started coming over every Monday night to play four handed bridge with Bob, his mother, and another friend named Dick Gill. Dick and Burnie both lived in a part of town called The Point. Dick lived up on the bluff and Burnie down below on the flats. Dick would pick Burnie up and they’d arrive at the Poole home together. The four of them, Mrs. Poole and the three teenage boys would spend several hours playing bridge. It went on all summer every Monday night until Bob left for college. He remembers the games as very relaxed and friendly. He has no recall as to how they came about. He’s still in touch with Dick Gill and asked him what he remembers. Dick remembers the games, but not how they got started. He didn’t think there was anything unusual about them.

I tell Bob that I think what happened was that when his folks heard Burnie was coming over to watch the game they panicked. Maybe they were aware of something going on in the community, that Bob wasn’t paying attention to, that made them feel particularly vulnerable. Could it have related to what had happened just a month before at the basketball game? Or that in combination with growing demands for civil rights in the community? I think because they were good people they immediately felt bad about their reaction and wanted to make amends for it. I think when Mrs. Poole got the idea of organizing a bridge night with the teenagers she was happy and relieved.

Bernie signed Bob’s yearbook over the photo of the Jr. Varsity basketball team where he is pictured in the back row, fourth player from the right. This is what he wrote:

Bob,

It’s been good getting to know you during the year. For such a brain you’re really a great guy. With your intelligence and personality you’ll go far in life. Lots of luck in everything you do.

Bernie (44)

PechaKucha

What is PechaKucha?

The PechaKucha 20x20 presentation format is a slide show of 20 images, each auto-advancing after 20 seconds. It’s non-stop and you've got 400 seconds to tell your story, with visuals guiding the way. PechaKucha was created in Japan in 2003 by renowned architects, Astrid Klein and Mark Dytham. The word “PechaKucha” is Japanese for “chit chat.”

About PechaKucha PVD

PechaKucha Providence hosts free monthly events where the Greater Providence community comes together to share ideas, creations, and stories using the PechaKucha format of 20 images that each last 20 seconds.

Yes, it's kind of like a "show and tell" for grown-ups.

Our always-open call for presenters ensures that no two PechaKucha Nights are the same. There’s a 100% chance that you will discover something new that you didn’t know you wanted to know. That’s the beauty of it.

What makes PechaKucha PVD Special?

Out of the 1,200+ cities across the globe that participate in PechaKucha, Providence is the second-longest consecutive running city to host an event, trailing only behind the founding city of Tokyo, Japan.

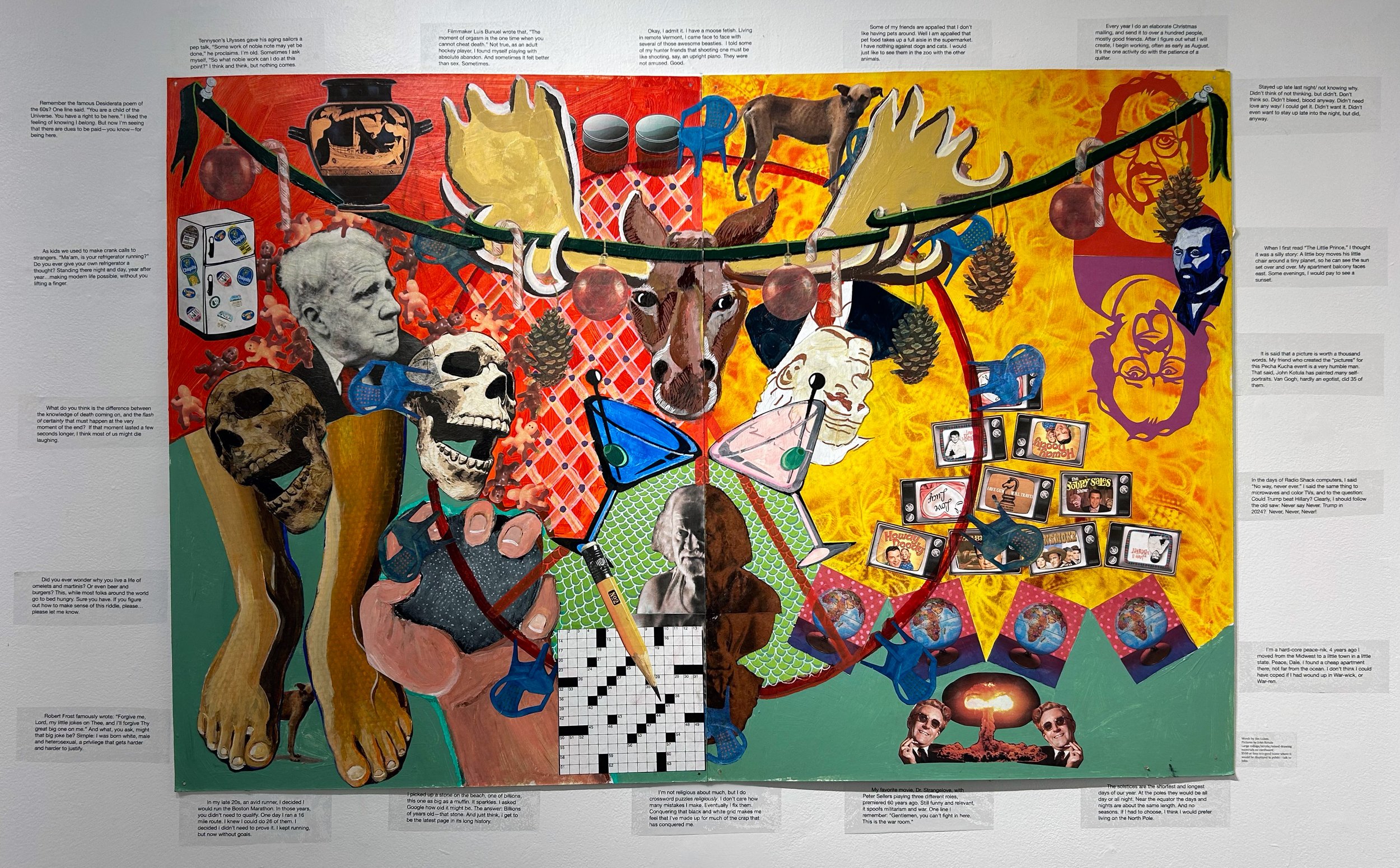

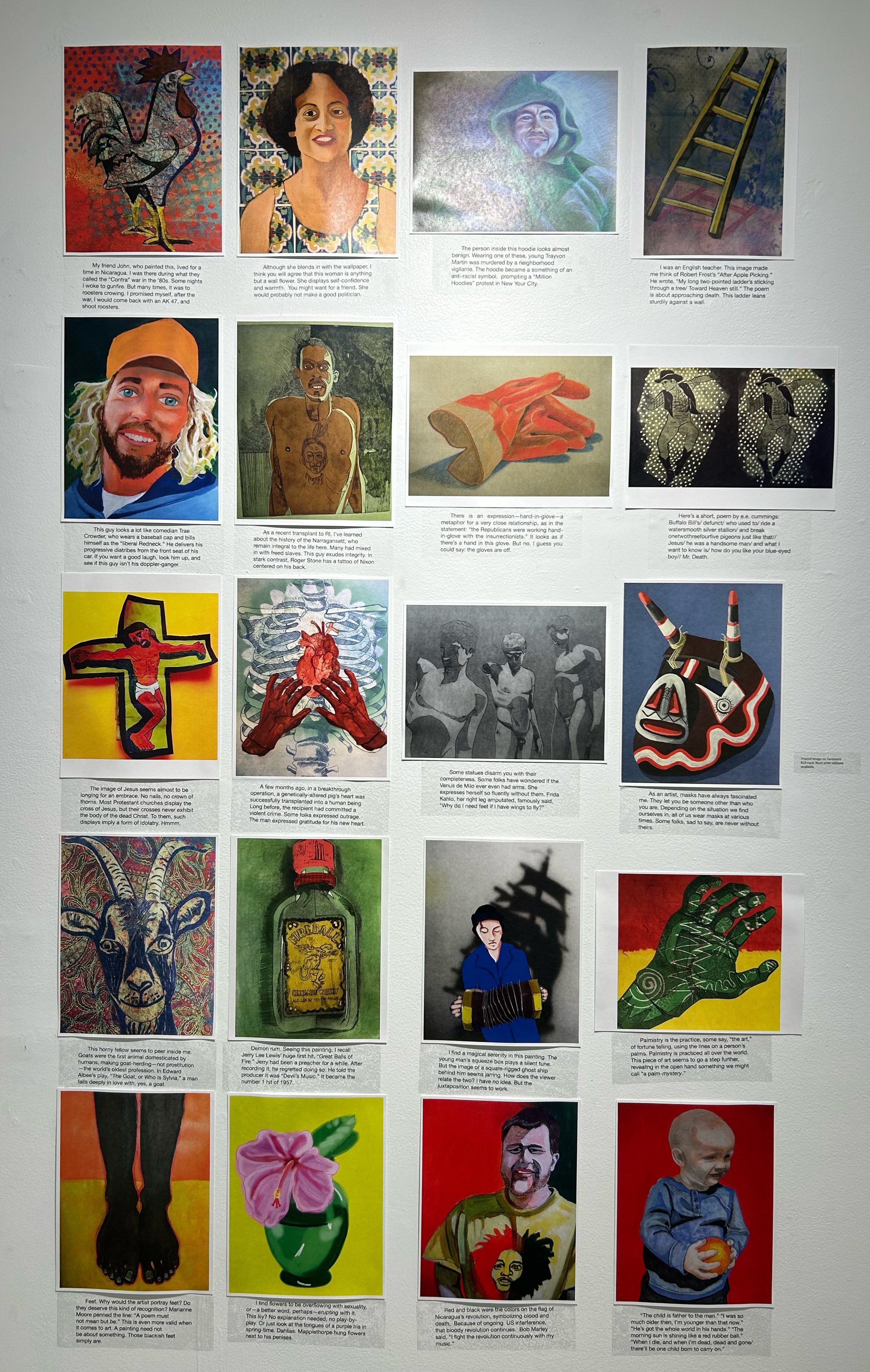

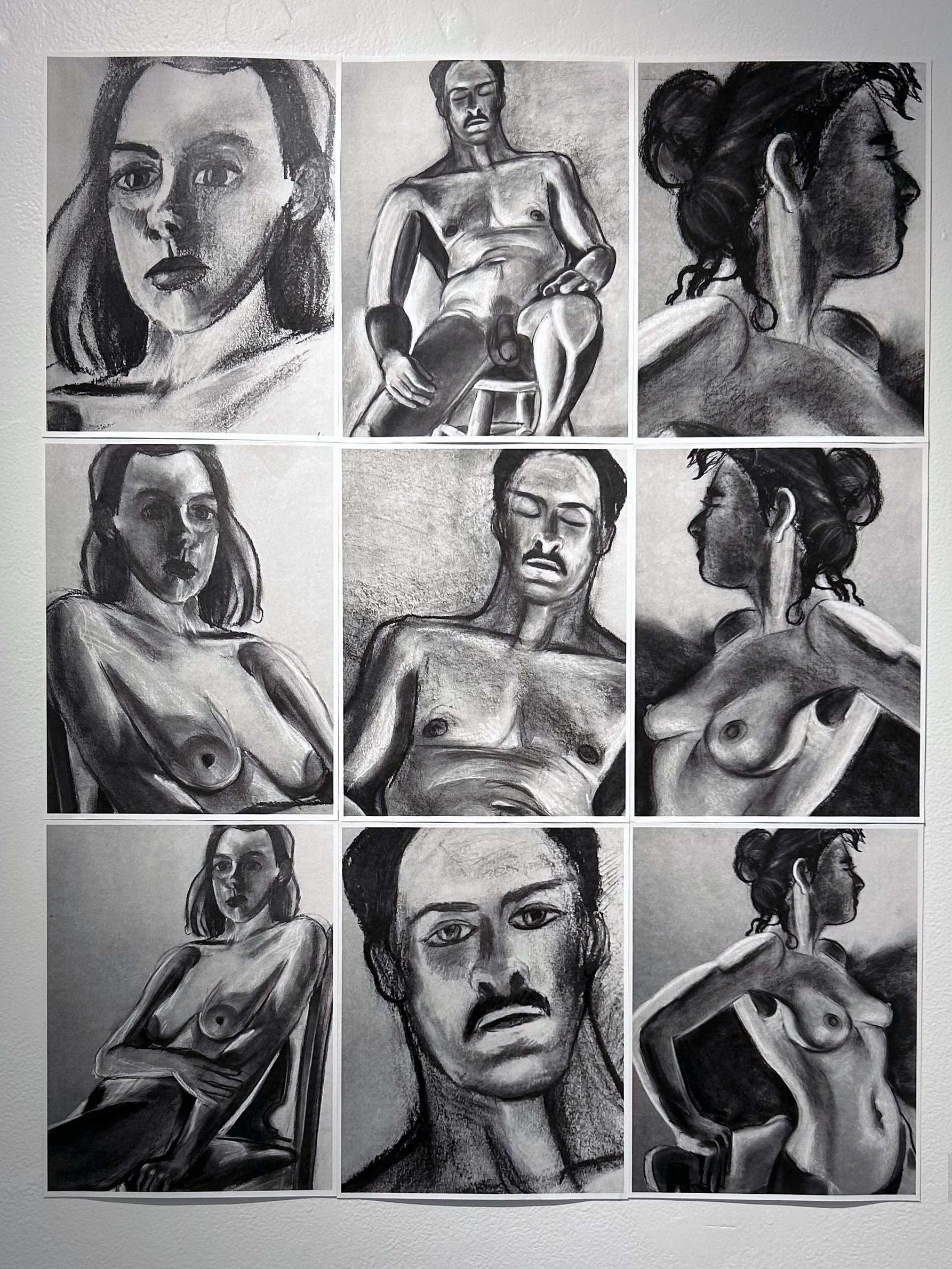

I love the PechaKucha presentation/story telling format for sharing my art and ideas.

On the video monitor you can watch two of my presentations. The next two big wall pieces are repurposed PechaKuchas that I did as a collaboration with my friend Jim Luken. For the first one, I gave Jim 20 pieces of my artwork and he wrote 20 second commentary to accompany them. For the second, Jim wrote, 20, 20 second prompts and I created the big painting to go with them. So, Pictures by John Kotula/Words by Jim Luken, followed by Words by Jim Luken/Pictures by John Kotula.